Giovanni Battista Tiepolo (1696–1770), Orpheus Rescuing Eurydice from the Underworld (ceiling detail), c. 1737–1738. Fresco, Palazzo Sandi-Porto (Cipollato), Venice.

Medieval specialist Edward Wheatley on the Orpheus Myth

Orpheus Victorious: A Short History

It has been said that everyone loves a happy ending, but what if literary history insists that certain tales such as that of Orpheus and Eurydice end tragically when he turns to look at her and she falls back into hell? Through the centuries writers have been willing to give their audiences what they want by inverting literary precedent, throwing out tragic endings and substituting happy ones, even in well-known ancient stories. Famous examples include Goethe’s Faust (1830), in which he rewrote the Faust legend with the soul-selling title character going to heaven rather than hell. Around 1680 Nahum Tate revised one of Shakespeare’s darkest tragedies, King Lear, expunging the ruler’s death and allowing him to see his daughter Cordelia (who is murdered in the Bard’s play) ascend to the throne with her husband Edgar. Centuries earlier, the tale of Orpheus and Eurydice underwent similar revision whereby the legendary musician successfully rescues his wife from hell. Jacopo Peri’s librettist Ottavio Rinuccini may well have known such a text.

Orpheus surrounded by animals. Ancient Roman floor mosaic, from Palermo. Museo archeologico regionale di Palermo, Palermo.

The story of Eurydice and Orpheus circulated as a myth in ancient Greece, but during the same period a version in which the musician successfully rescues his wife also appeared. (This text was known by the English Renaissance poet Sir Edmund Spenser, and it influenced episodes in The Faerie Queene.) However, the story of Orpheus losing Eurydice during their ascent from hell had a much higher profile in ancient Rome because it was retold in the works of two of the giants of Latin literature, Virgil and Ovid. The Georgics and the Metamorphoses remained central to the literary canon throughout the Middle Ages and the Renaissance in both the original Latin and in multiple translations in many different languages.

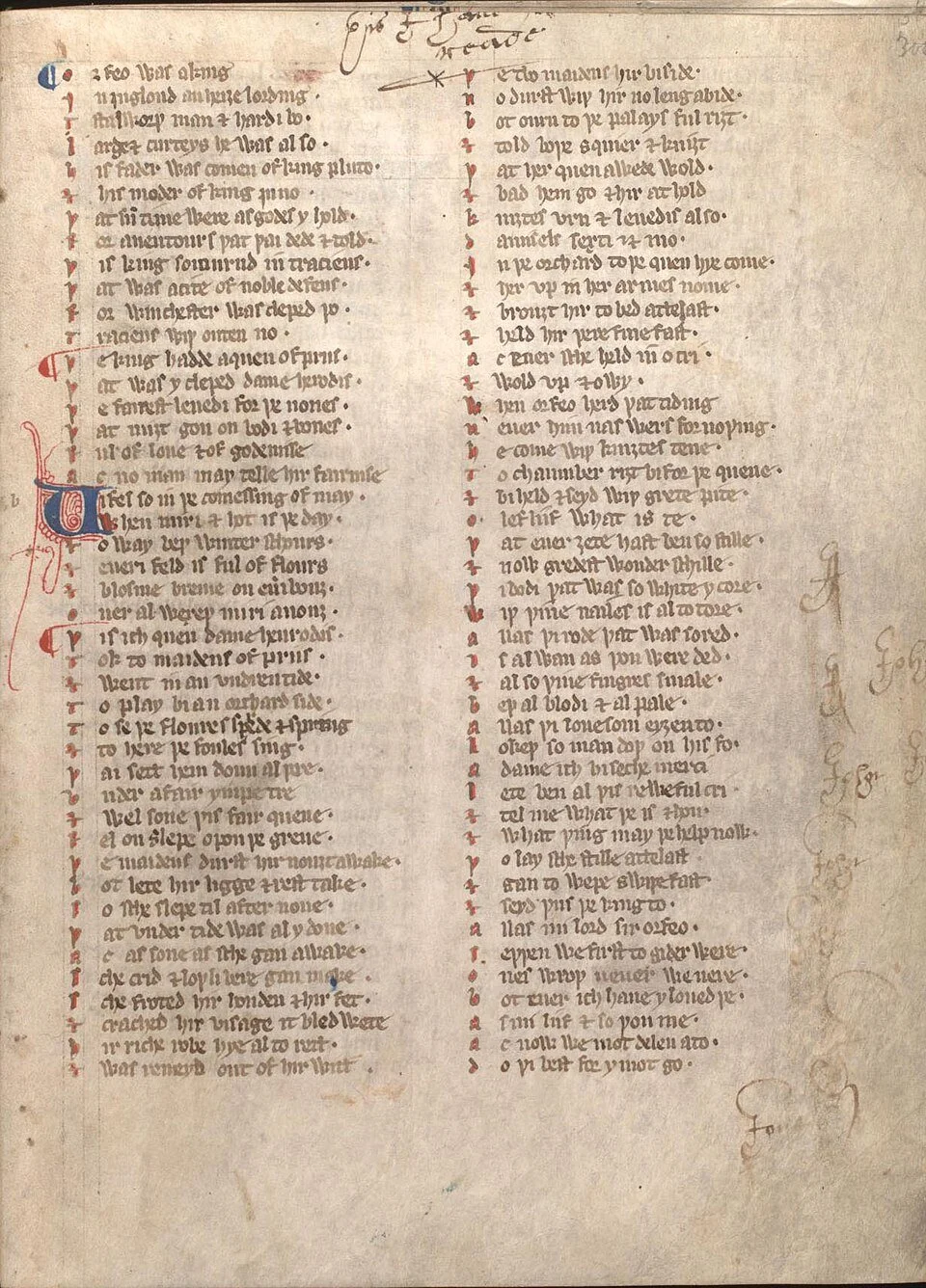

Sir Orfeo, first page, c. 1340. Auchinleck Manuscript (Advocates 19.2.1), National Library of Scotland, Edinburgh.

An anonymous poem from the Middle Ages called Sir Orfeo (ca. 1320), which actually has two closely related happy endings, attracted the attention of none other than J. R. R. Tolkien; it was one of only three Middle English poems that he translated into modern English. Here Orfeo is not only a consummate musician but also king of England, so when his wife, here called Herodis, is taken to a hellish underworld, her disappearance has both romantic and political implications. When Orfeo is leaving his kingdom to rescue her, he appoints a steward to rule the kingdom in his absence. Conventionally in Middle English literature such a character proves untrustworthy and attempts to retain permanently the power that he has been given only temporarily, but such is not the case here. Because Orfeo’s search for Herodis is lengthy, he is unrecognizable when he returns to his court with her. In order to test the steward, he shows him Orfeo’s harp and claims to have found it next to a corpse that had been devoured by lions and wolves. Taken in by the lie, the steward weeps and bemoans the death of his master, and his intense grief causes him to faint. Orfeo sees that the steward has remained faithful to him, so he reveals his true identity to the court and takes control of the throne again. Here the harmonious reestablishment of Orfeo’s relationship with Herodis clearly foreshadows the reestablishment of political order in the kingdom.

Several other examples of the happy ending of the legend survive from the Middle Ages, though in some the happiness is relative. Around 1309 a writer known as Peter of Paris revised not just the ending but the cause of Eurydice’s death, which in most versions was attributed to a snake bite. Peter writes, “And it happened that Orpheus’s wife nagged him, and the rancor between them grew so extreme that he struck her and killed her.” Orpheus grows remorseful and decides to seek her in hell, “because he knew very well she was there,” snipes the sardonic writer. The ending of this version of the tale is only happyish: “The gods of the underworld gave his wife back to him with a covenant that he would never see the heavens and would be blind forever.” This punishment along with the possibility of renewed nagging makes for a less-than-euphoric ending. Thierry of Trond has his literary-historical cake and eats it, too: in his version Orpheus looks back and loses Eurydice, but he “returns again to the desolation of the pit” and “bravely he took what he desired from Styx by force.” Another medieval writer says that at the command of the god of love, Amor, Orpheus’s wife is given back to him.

Peri, Jacopo. L’Euridice. Firenze: Cosimo Giunti, 1600. First-edition libretto, held at The Newberry Library, Chicago.

Of course Peri’s opera ends happily, as do others later in the 17th century. Peri’s collaborator, Giulio Caccini, recycled Rinucci’s libretto in his opera of 1602, leaving the happy ending in place. In Claudio Monteverdi’s opera (1607), Orfeo looks back and loses Euridice, but Apollo, in true deus ex machina fashion, intervenes and takes the couple to heaven, clearly an allusion to the happy Christian afterlife. Luigi Rossi’s Orfeo of 1647 chooses a different pagan deity to resolve the plot: after Orfeo loses Euridice, Jupiter tells him that he, his wife, and his lyre will be transformed into constellations. Mercury then appears in order to explain that the triple apotheosis represents the resurrection of Christ, an allegorization that ties the Orpheus legend even more closely to Christianity. In the 18th century the best-known opera based on the legend also used a deity to intervene: in C. W. Gluck’s Orfeo ed Euridice (1762), when Orfeo looks back at her, she dies. Amor appears, revives her, and they return to Earth to join in a triumphal chorus celebrating the power of love.

A triumphal chorus—in opera, isn’t that the happiest of endings? The happy (or even half-happy) resolutions in literary versions of the Orpheus legend bring with them a certain kind of satisfaction, but tragic endings can do the same. However, reading is controlled by readers, and time is not of the essence; they can read slowly or quickly, pick up and put down the book, or choose not to read the ending at all. Opera is different because it takes place in real time: the audience is with the performance in the moment and does not control what happens on stage. The composer and librettist must decide what to give them. How about an elegiac chorus bemoaning the loss of Eurydice? Or even Orpheus alone onstage singing a regretful, mournful dirge? In the hands of a great composer, these endings would (and did) provide a particular kind of closure. But why not a felicitous finale with a triumphal chorus instead? While Rinucci and Peri were putting together this opera, they must have understood that such a joyous musical conclusion would provide both a happy ending and a happy beginning: Euridice celebrates the title character’s rebirth as well as the birth of a new genre that would dramatically change the future of musical performance.

Learn more about Haymarket Opera Company and The Newberry Consort’s 2025 performance of Peri’s Euridice.

About the author

Edward Wheatley is professor emeritus of English at Loyola University Chicago, where he specialized in medieval literature, the history of the book, drama, and disability studies. His most recent book, Stumbling Blocks Before the Blind: Medieval Constructions of Disability, examines representations of blindness in medieval England and France. He has served as the classical-music reviewer for the Charlottesville Daily Progress for five years.

About The Haymarket Review: This new digital publication including thoughts about the work produced by Haymarket is designed to deepen our connection to audiences, nurture and feed audience curiosity about historical performance, offer critical opinions and thoughtful reflections on our performances, and provide a forum for Haymarket and its audience to connect through sharing insights, opinions, learning, and expertise.